What Are Critical Minerals and Why Do They Matter?

Of the thousands of known mineral species, some are particularly valuable to modern technology—and by extension to modern economies—and are therefore classified as critical minerals. As the name suggests, these minerals are considered to be critical to key industries and national security. Large economies throughout the world publish lists of critical minerals, identifying which resources they believe are essential to their national interests.

There is no universally accepted definition of what makes a mineral “critical,” and while many national lists overlap, the justification for including a given mineral often differs from country to country. What these lists share, broadly, is a recognition that these minerals underpin strategic industries and face elevated risks of supply disruption.

The United States, the European Union, Japan, and Australia share 17 specifically named minerals in common. That shared list includes Antimony, Beryllium, Bismuth, Cobalt, Gallium, Germanium, Hafnium, Lithium, Magnesium, Manganese, Nickel, Niobium, Silicon, Tantalum, Titanium, Tungsten, and Vanadium [1, 2,3,4]. All the lists also include, by name or by group, rare earth elements (REEs). These elements are a distinct group because of their unique properties. Although quite plentiful throughout the crust, REEs rarely occur on their own and so require extensive processing to isolate and purify. REEs are included with other critical minerals because of their diverse applications from catalytic converters and flame retardants to rechargeable batteries, semiconductors and permanent magnets. Securing steady supplies of critical minerals is essential not only for consumer products, but also for agriculture, medical technologies, and military systems.

As technologies evolve and geopolitical conditions shift, critical mineral lists are periodically updated following extensive research and risk assessment. Most now contain more than 30 entries, a reflection of how deeply mineral supply has become entangled with global politics.

Geological Constraints and the Concentration of Global Supply

The complexity of critical mineral supply is strongly influenced by geology. Some countries sit atop rich mineral deposits, while others have very little to mine or none at all. Over time, a combination of natural endowment, sustained investment, and industrial infrastructure has concentrated mining and refining in a small number of locations.

For many critical minerals, more than half of global production is controlled by a single country. This concentration leaves supply chains exposed. Political instability, trade disputes, or domestic slowdowns in one country can ripple outward, disrupting industries worldwide and driving sudden price swings.

Geopolitical Risk and Strategic Vulnerability

Among the 17 minerals shared across major economies’ critical lists, ten are primarily produced by China. Nine are produced either primarily or secondarily by Russia, while two (cobalt and tantalum) are sourced from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Each of these countries has experienced recent or long-running disruptions that have translated into higher prices and market volatility.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, for example, triggered historic price spikes of nickel as buyers feared sanctions and tariffs would cut off access to trade. The DRC, one of the largest and most populous countries in Africa, has been enduring extreme internal conflict for decades. This has meant that its considerable mineral reserves are under-utilized and production relies heavily on outside investment. Because the political environment of the country is far from settled, there remains an ongoing threat to any industry.

China occupies a uniquely powerful position in the critical minerals ecosystem. In addition to hosting significant domestic reserves, China has invested heavily in mining and refining infrastructure both domestically and internationally. Even when a mineral is not mined domestically, China is often a dominant refiner or investor, giving it significant leverage in global trade. In an effort to decrease this reliance, U.S. foreign policy has recently leaned heavily on tariffs, creating significant volatility in minerals majorly controlled or produced by China [5].

Government Responses and the Push for Supply Chain Resilience

Concerns about supply security and price volatility have increasingly shaped government policy. Cobalt illustrates the issue clearly. While nearly all known cobalt reserves are located in the DRC, roughly half of the country’s largest cobalt mines are owned by Chinese companies [6]. This foothold is the result of sustained investment and diplomatic engagement by China across sub-Saharan Africa over several decades.

In contrast, the European Union—where domestic production of critical minerals is limited—has leaned heavily on trade partnerships and international cooperation to secure access. In the United States, the response has included a $12 billion Critical Minerals Stockpile, designed to stabilize prices and protect domestic industry as the country reduces its reliance on China for key inputs [7].

Although the U.S. has substantial mineral reserves and refining capacity of its own, intensifying geopolitical competition has accelerated efforts to diversify supply and invest in advanced processing technologies capable of refining critical minerals at scale.

Refining as the Bottleneck in Critical Mineral Supply Chains

While mining often dominates public attention, refining frequently represents the true bottleneck in critical mineral supply chains. Many critical minerals occur at low concentrations, exhibit similar chemical behavior to abundant elements, or are embedded within complex mineral matrices. Extracting them at sufficient purity and scale requires advanced separation and refining technologies capable of delivering high selectivity, yield, and operational reliability.

In many cases, refining capacity is more geographically concentrated than mining itself. Even when raw minerals originate from diverse regions, they are often shipped to a limited number of countries for processing. These chokepoints amplify geopolitical risk and increase vulnerability to supply disruptions. As a result, expanding domestic and allied refining capacity has become a strategic priority for governments and manufacturers alike.

IBC Advanced Technologies, Inc. addresses this challenge through the development and deployment of highly selective separation technologies for critical minerals. Drawing on decades of expertise in highly selective metal separations, IBC designs refining processes capable of isolating high-value elements from complex feed streams, enabling efficient production of minerals essential to energy storage, electronics, defense systems, and advanced manufacturing.

Molecular Recognition Technology™ (MRT™): Precision Separation at Industrial Scale

At the core of IBC’s refining capabilities is Molecular Recognition Technology™ (MRT™), a platform based on highly selective ligand systems immobilized within robust inorganic or polymeric resin beads. Unlike conventional hydrometallurgical techniques, such as ion exchange, solvent extraction and precipitation, that rely primarily on broad chemical differences, MRT™ operates through molecular-level recognition. This enables target ions to be captured with exceptional selectivity even in the presence of chemically similar species.

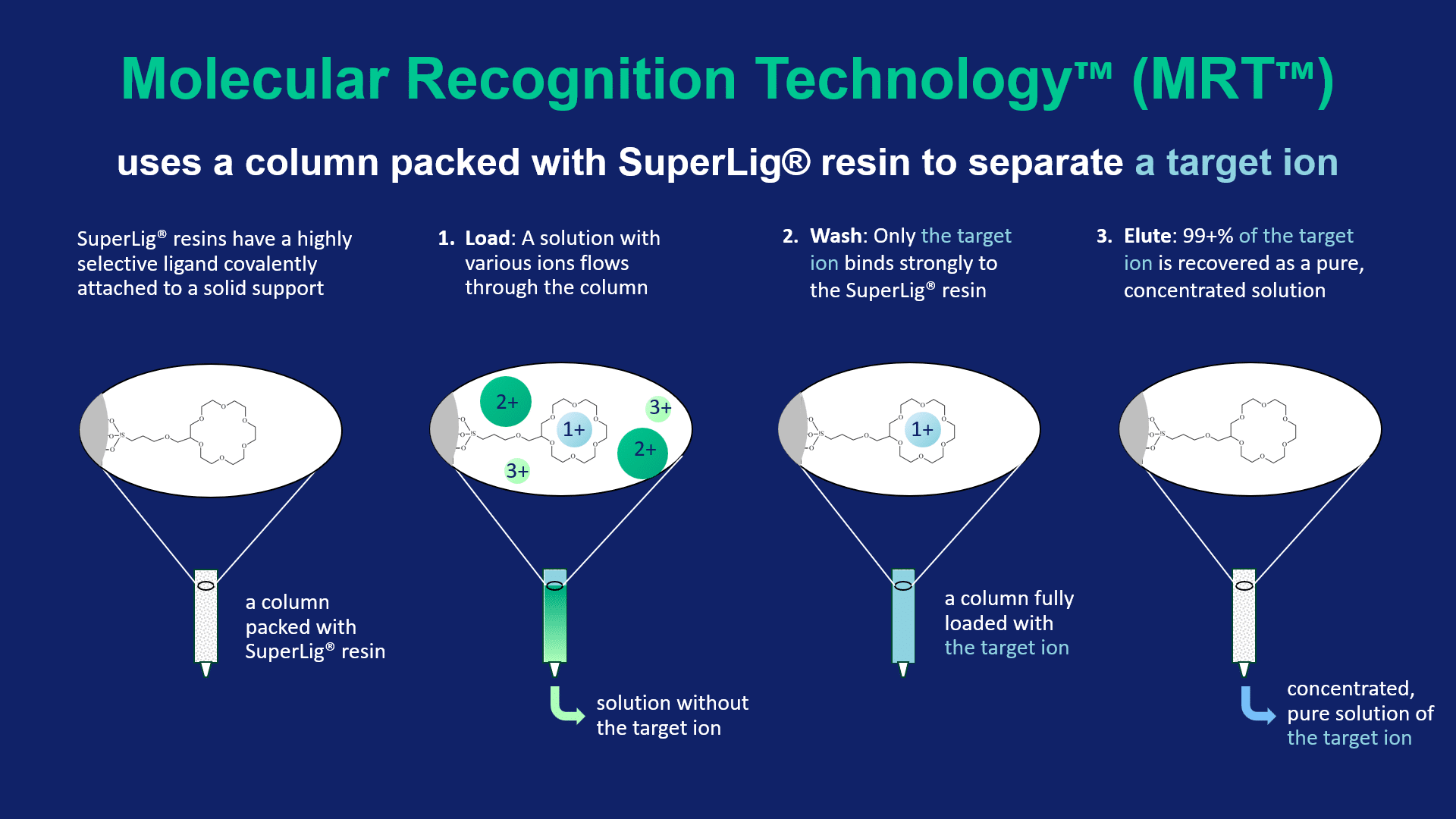

MRT™ separations are typically implemented using compact, column-based systems that operate through a simple, repeatable cycle:

- Loading phase: The feed solution is passed through a column packed with SuperLig® resin beads, to which the target ion selectively and rapidly binds.

- Pre-elution wash phase: Any remaining feed is washed from the column, removing unbound components.

- Elution phase: The target ion is eluted using a small amount of eluent, producing a highly pure, concentrated solution.

- Post-elution wash phase: Any residual eluent is washed from the column, preparing the system for the next loading cycle.

This process enables exceptionally high selectivity and recovery while minimizing reagent consumption, waste generation, and equipment footprint. The result is a highly efficient refining platform that delivers both environmental and economic advantages.

Scalable Refining Solutions for Strategic and Critical Minerals

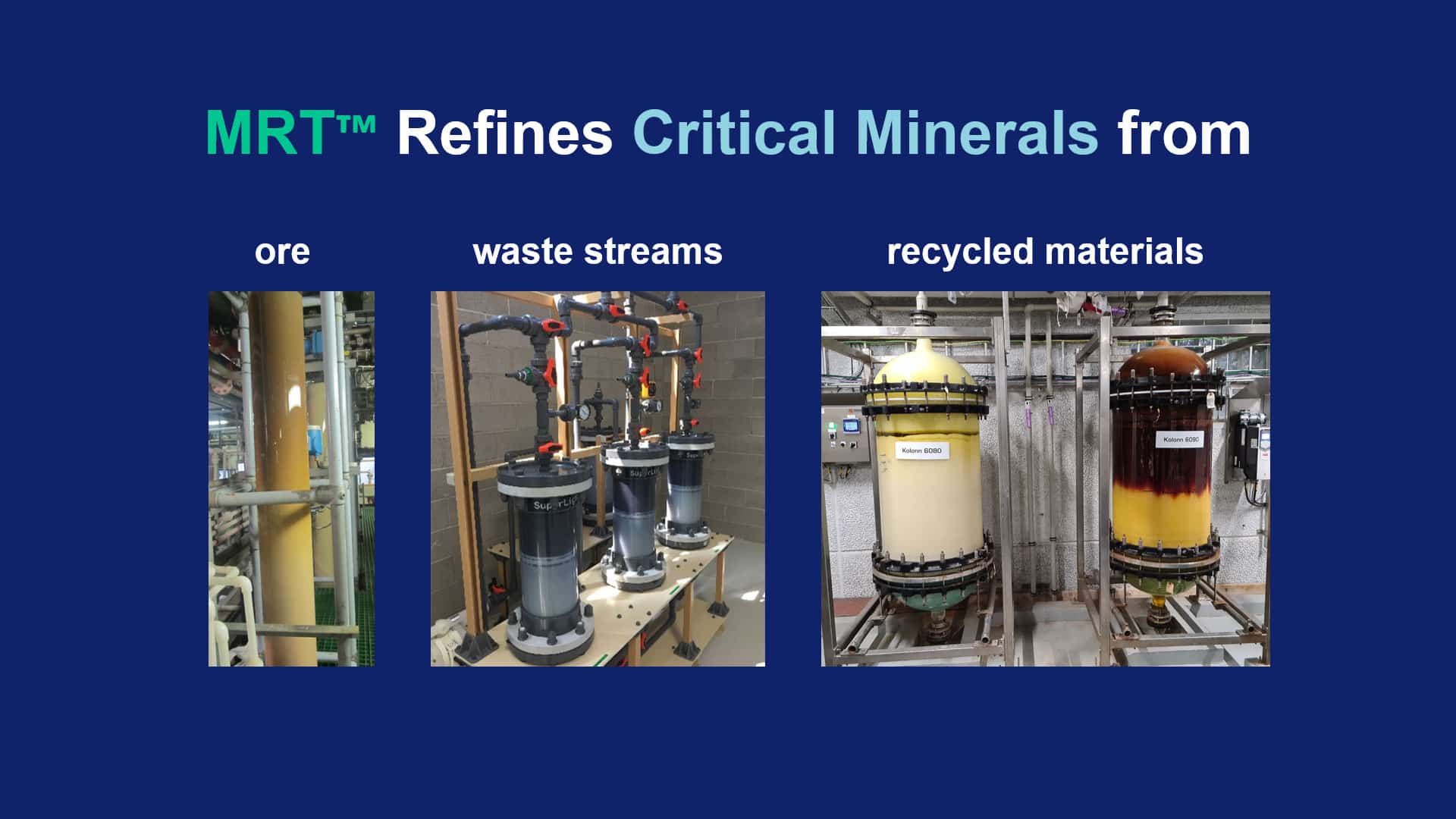

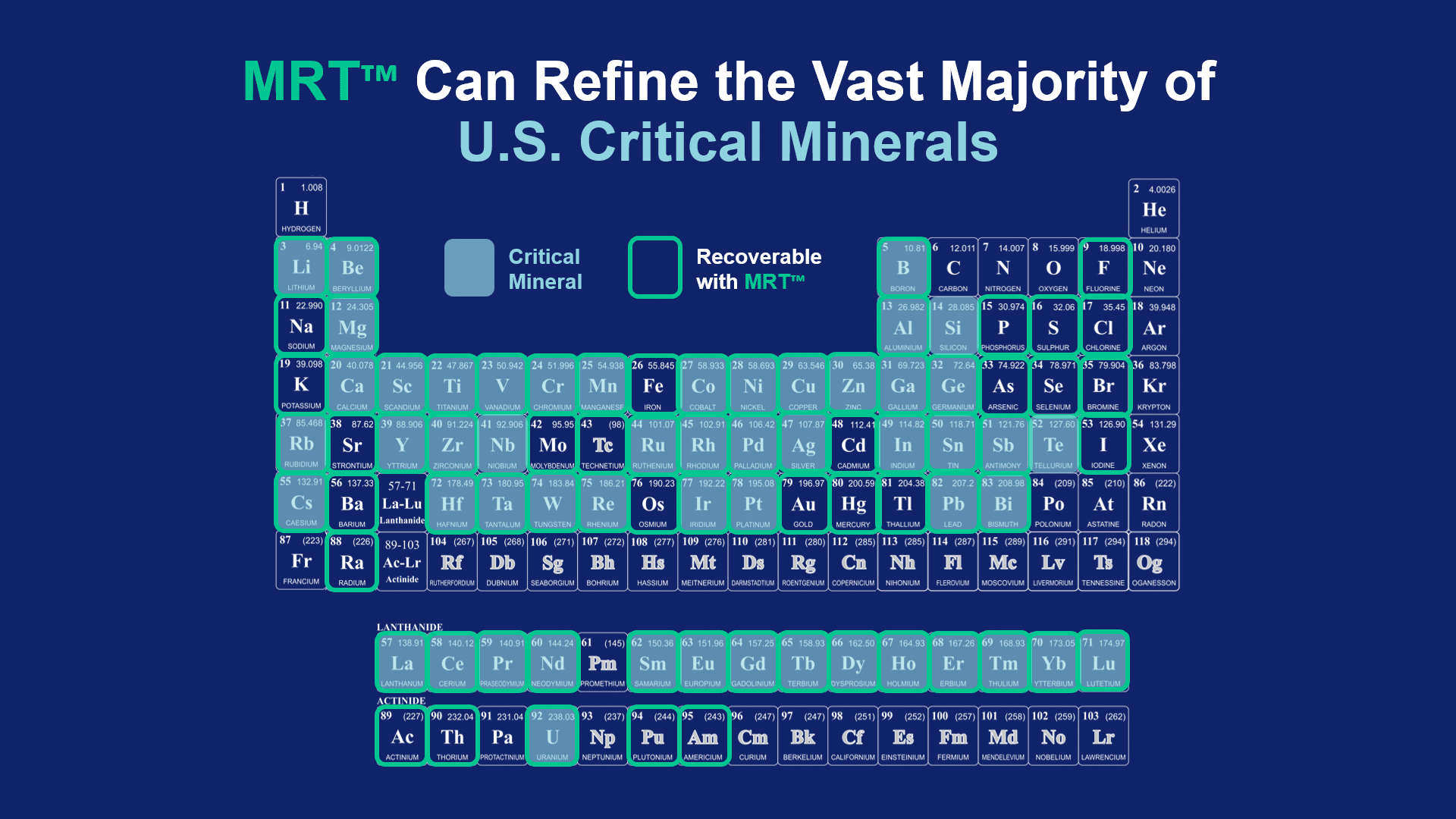

IBC has applied MRT™ across a broad range of critical mineral separations, including rare earth elements, platinum group metals, battery metals, and strategic base metals. MRT™ is particularly well suited for refining low-concentration feed streams, recycling secondary sources, and purifying metals that exhibit highly similar chemical properties.

MRT™-based refining systems are inherently scalable and adaptable to a wide variety of production environments. Their modular, column-based design allows rapid deployment, seamless integration into existing process flows, and straightforward expansion as demand grows. High selectivity reduces downstream processing requirements, while minimal reagent usage lowers waste generation, simplifying regulatory compliance and lowering total operating costs.

As governments and manufacturers seek to strengthen domestic supply chains and reduce reliance on geopolitically concentrated refining capacity, MRT™ offers a unique, advanced separation technology that provides a practical, economic pathway toward resilient, scalable production of critical minerals.

References

[1] Interior Department releases final 2025 List of Critical Minerals. USGS. https://www.usgs.gov/news/science-snippet/interior-department-releases-final-2025-list-critical-minerals

[2] Australia’s Critical Minerals List and Strategic Materials List. Critical Minerals Office. https://www.industry.gov.au/publications/australias-critical-minerals-list-and-strategic-materials-list

[3] Japan. Mineral prices. https://mineralprices.com/critical-minerals/japan/

[4] Critical raw materials. European Commission. https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/sectors/raw-materials/areas-specific-interest/critical-raw-materials_en

[5] Besada H., D’Alessandro, C. (2025, October 7). Tariffs, trade, and critical minerals stand in the crosshairs of US-China rivalry. The London School of Economics and Political Science. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/africaatlse/2025/10/07/tariffs-trade-and-critical-minerals-stand-in-the-crosshairs-of-us-china-rivalry/#:~:text=Tariffs%2C%20subsidies%2C%20and%20strategic%20framing,Africa%2C%20from%20Zambia%20to%20Angola.

[6] Gregory, F., & Milas, P. (2024, October 17). China in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: A new dynamic in critical mineral procureme. US Army War College – Strategic Studies Institute. https://ssi.armywarcollege.edu/SSI-Media/Recent-Publications/Article/3938204/china-in-the-democratic-republic-of-the-congo-a-new-dynamic-in-critical-mineral/

[7] Dlouhy, J., & Deaux, J. (2026, February 2). Trump to Launch $12 Billion Critical Mineral Stockpile to Blunt Reliance on China. Bloomberg. https://finance.yahoo.com/news/trump-launches-12-billion-minerals-120104530.html